This post is to introduce my process for writing a memoir on pain and the onset of lupus in a catastrophic first flare; I should, according to Captain Obvious’s Taser or some such rule of mainstream logic, use the phrase “chronic illness” instead of “health issues.” But I resist defining such an integral part of my being as “illness.” I had nearly three years of being truly limited, and that was enough, thanks. I am now feeling well, largely because I have modified my lifestyle to keep illness at bay; yet, I still “have lupus.” So, do I suffer from chronic illness? Or do I negotiate chronic issues to maintain good health? These are real questions, and not just a semantic exercise to be blasted apart by Captain Obvious’s limited understanding.

But, pardon me. I digress. I wanted to talk about books.

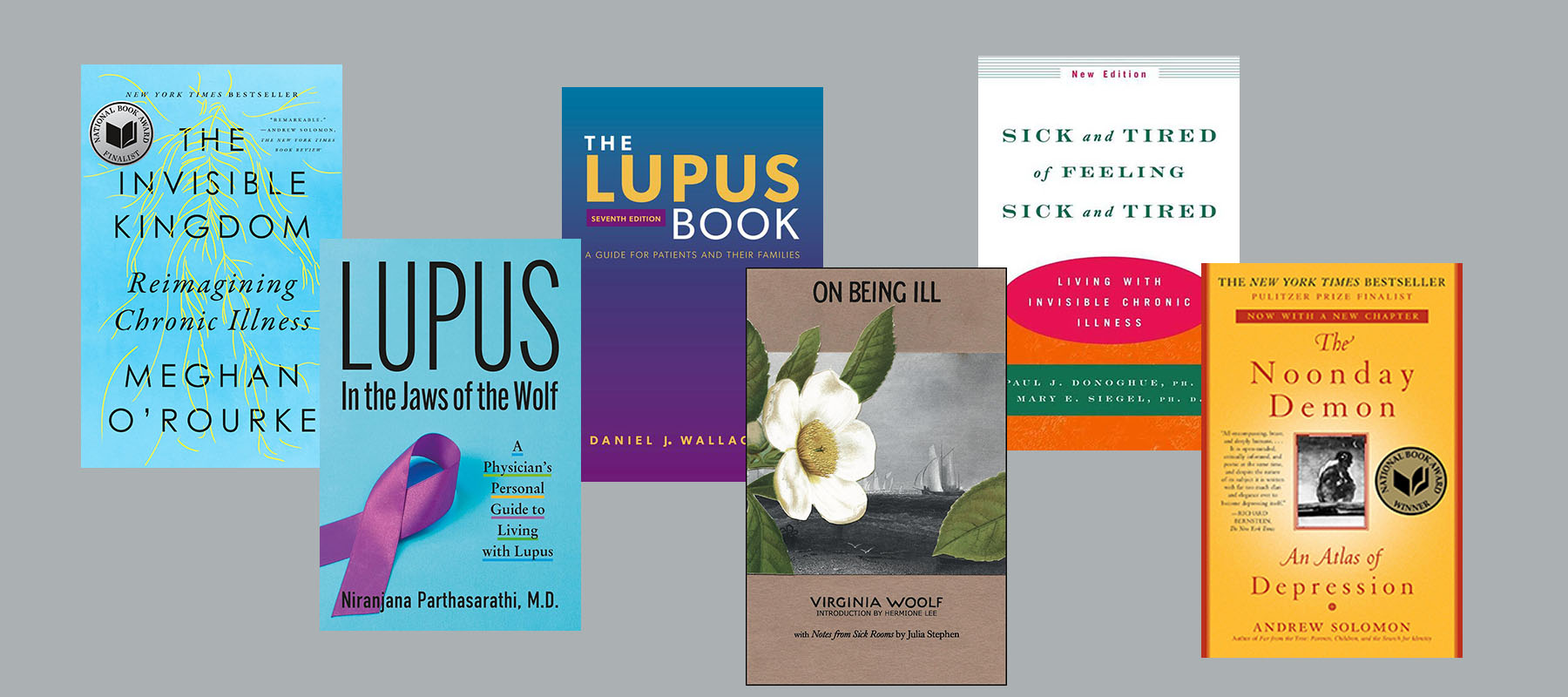

I don’t think I could commit to a long form work about my experiences without a lot of books to help along the way. The full list is much longer than I could share in a single post! But here are a few titles I loved—and little peeks into why they’ve been important to my work.

Links to purchase are to Amazon and Bookshop.org.

The Invisible Kingdom: Reimagining Chronic Illness by Meghan O’Rourke (New York: Riverhead Books, 2022). O’Rourke sets herself a high bar: to address “patients, family members, and medical professionals, as well as anyone who has faced the challenges of trying to identify an elusive condition. . . . [The book] aims to find language for a lived experience that in some ways resists description, to show how our culture tends to psychologize diseases it doesn’t yet understand, and to explain how and why our medical system, for all its extraordinary capabilities, is ill equipped to handle the steep rise in this kind of chronic illness.”

O’Rourke also points out, though, that “I am not telling this story because I think my illness experience is extraordinary. On the contrary, what happened to me is quite common . . . . But it is the very ordinariness of my story that made it feel important to share.” This is a well researched, highly literary work — minutely attentive, in other words, to both fact and language — and it is uniquely relevant to readers like me, highly educated, economically privileged, but still, subject to the vagaries of life with an invisible health condition. Megan O’Rourke didn’t answer all my questions, but as she delved into her own pain and frustration, and her struggles with the meager information available to explain invisible ailments, she reassured me that all of us have more questions than answers.

The Lupus Book: A Guide for Patients and Their Families, 6th edition, by Daniel J. Wallace MD (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019). When I learned that I might have lupus, I really didn’t know what to think. I had to start taking immunosuppressants—would I have to approach life like the boy in the plastic bubble? When the first level of immunosuppressants didn’t work, I wondered whether I had been misdiagnosed, and if so, what else could be wrong with me—what would a differential diagnosis of someone with my symptoms be? Even if I’d been diagnosed correctly, how should I judge whether one therapy was more likely to work than another? What online resources could I trust to back up (or call into question) the ideas presented by my doctors?

When one of your main symptoms is pea-soup brain fog, these questions become even harder to consider. Dr. Wallace’s frank, thorough treatment of lupus, including a big fat list of online authorities to explore, did a lot to dispel my confusion, fear, and anxiety. It’s incredible how many questions he is able to answer in a relatively brief book, in straightforward, clear prose, supplemented with well-organized tables. I was so excited about this book that I got a copy for my mother, just so that we could talk about it. It’s become my lupus bible.

Lupus: In the Jaws of the Wolf–A Physician’s Personal Guide to Living with Lupus by Niranjana Parthasarathi MD (N.p.: self-published, 2023). Dr. Partha, as she is affectionately known, has published a uniquely helpful memoir on lupus, as she is a physician and also a professor of internal medicine. Anyone who has been made to feel guilty about “triggering” their own lupus flares due to lifestyle choices will empathize with Dr. Partha’s experiences as she relates being diagnosed with lupus in medical school, navigating family and social pressure to give up her dream and adopt a less “stressful” lifestyle, and dealing with the inevitable flares that affected multiple organ systems and devastated her body over and over.

Through it all, although continually haunted by the self-blame that arises naturally in so many of us, Dr. Partha remained true to her calling and refused to let self-blame rule her life. In the Jaws of the Wolf includes extensive, helpful notes on practical self-care. Whenever I wonder whether I should step back from my personal goals, I think of Dr. Partha (“What would Dr. Partha do?”) and remember to follow my best intentions, instead of my fears.

The Noonday Demon by Andrew Solomon (New York: Scribner, 2015). This is a well-known book about depression, that most devastating of invisible chronic conditions. It resonated so powerfully for me that I remain quietly surprised at how seldom we include depression in our conversations that compare lupus with a host of other conditions. While we do acknowledge that those of us with lupus can also suffer depression, we don’t often draw parallels between the experiences of those with “just” lupus and those with “just” depression. Let me be the first to tell you, if you don’t already know: if you have lupus, or any other chronic condition that limits you according to mainstream definitions, you need to acknowledge its effects on your mental health. Please consider Solomon’s in-depth account, and what it might have in common with your experience.

On Being Ill by Virginia Woolf (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2021). I placed this list in alphabetical order; On Being Ill follows The Noonday Demon serendipitously, yet appropriately—Virginia Woolf famously died by her own hand. Less famously, her long-term health issues involved “persistent, periodical illnesses, in which mental and physical symptoms seemed inextricably intertwined. . . . It seems possible, though unprovable, that she might have had some chronic febrile or tubercular illness. It may also be possible that the drugs she was taking, for both her physical and mental symptoms, exacerbated her poor health” (Hermione Lee, from the introduction).

This vague account of symptoms in someone who suffered profoundly will sound familiar to most of us with chronic health conditions. Yet, it is the humor in Woolf’s essay that most draws me in—how she reaches for language to describe what we with chronic conditions experience as indescribable pain, indescribable weariness. “English, which can express the thoughts of Hamlet and the tragedy of Lear, has no words for the shiver and the headache. . . . The merest schoolgirl, when she falls in love, has Shakespeare or Keats to speak her mind for her; but let a sufferer try to describe a pain in his head to a doctor and language at once runs dry. There is nothing ready made for him. He is forced to coin words himself, and, taking his pain in one hand, and a lump of pure sounds in the other (as perhaps the people of Babel did in the beginning), so to crush them together that a brand new word in the end drops out.” In this way, On Being Ill favors, admittedly, the reader who is also a lover of writing as an art. But those who are interested in delving further will find, in this edition, not only the context-defining introduction by Hermione Lee, but also Notes from Sick Rooms by Julia Stephens, Woolf’s mother, who frequently cared for the ill and represented for many the Victorian feminine ideal of “the angel in the house”—an ideal that Woolf, for one, denounced, in her time. Post-Victorian period series on chronic illness, anyone?

Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired: Living with Invisible Chronic Illness by Paul J. Donoghue PhD and Mary E. Siegel PhD (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000). Although the newest edition is over twenty years old, Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired doesn’t feel dated. Written in an easy-to-devour, self-help style, it’s nonetheless full of complex insight into what you might experience after a new diagnosis of chronic health issues.

I personally love the vignettes that the authors include from their practice, which cover all kinds of day-to-day conflicts that arise after diagnosis with an invisible chronic illness (ICI), including those that arise in relationships when one partner’s needs drastically change; the uncertainty and frustration that can arise in the workplace when one team member asks for a new work-life balance; and the micro-hostilities that we might encounter when our doctors, friends, and family members don’t quite understand what’s wrong, and we don’t quite know what to tell them. The book also describes, generally, some of the conditions that can be defined as ICIs, including lupus, while acknowledging that the list is by no means limited to identifiable conditions.

In the words of Donoghue and Siegel’s Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired, “Acceptance means admitting the truth of being sick or tired and then deciding what action is most beneficial. It means having the courage to admit at times that you can’t do it, whatever the it is, and the courage to say no. Denial of the truth, denial of limits leads to self-destructive actions as well as alienation from oneself and an inauthentic way of being.” This is where my work in progress begins—with understanding the need to get to acceptance. Can we get to acceptance without first dealing ourselves the blows of denial? That’s the question that I must ask and answer on this journey.

You must be logged in to post a comment.